Born in Andalusia, Alabama, in 1930, Justice Hugh Maddox has enjoyed a remarkable career. He graduated in Journalism from the University of Alabama in 1952, having been a writer, columnist, and an associate editor of the Crimson White, after which he served two years in the Air Force before coming here to Law School. Having graduated from law school in 1957, he began a legal career which included clerkships for Judge Aubrey Cates of the Alabama Court of Appeals and Judge Frank M. Johnson of the United States Court for the Middle District of Alabama. Interestingly, he later (1964-1969) served as an advisor to Governors George C. Wallace, Lurleen B. Wallace, and Albert P. Brewer. Subsequently he served (1969-2001) as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama.

In the early 1970s, Maddox read books and told stories to his little daughter Jane. She liked his stories, so he decided to write and illustrate one for her. The subject that he chose, “crop diversification,” may not be an obvious choice for a child’s book. But Maddox was trying to dramatize a turning point of twentieth-century Alabama history, and he would do so by following the path blazed by Aesop’s talking animals. The artwork was no problem for Maddox, who had long enjoyed drawing and painting, and was known to keep India ink, a pen, and clean paper in his office.

In the early 1970s, Maddox read books and told stories to his little daughter Jane. She liked his stories, so he decided to write and illustrate one for her. The subject that he chose, “crop diversification,” may not be an obvious choice for a child’s book. But Maddox was trying to dramatize a turning point of twentieth-century Alabama history, and he would do so by following the path blazed by Aesop’s talking animals. The artwork was no problem for Maddox, who had long enjoyed drawing and painting, and was known to keep India ink, a pen, and clean paper in his office.

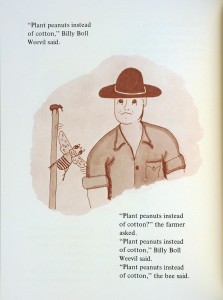

The result, first published in 1976, was Billy Boll Weevil: A Pest Becomes a Hero. The text and drawings follow Billy in his quest to make friends with a farm family. We meet Billy’s grandfather and other creatures, including a kindly bee who tells Billy to “Do something good” for the farmer. Of course Billy and his kindred can’t very well stop feeding on cotton plants—a collective appetite which had brought the south’s economy to the verge of collapse in the early twentieth century. So instead Billy follows the bee’s suggestion and tells the farmer to start planting peanuts. The farmer takes the hint. Before long Billy is a hero, and the local people have put up a monument to him (as indeed happened in 1919 in Enterprise, Alabama).

Not many writers have made use of talking insects—apart from Lewis Carroll, who employed an articulate caterpillar in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and a melancholy gnat in Through the Looking Glass. Maddox pulls it off by keeping his dialogue simple, almost formulaic. “When you write children’s books,” he once said, “you’ve got to put yourself back in a child’s position.” Thus, as Montgomery Advertiser reporter Kelly Dowe observed of Billy: “He cries when he is sad. He runs when he is afraid.”

Justice Maddox has reissued Billy Boll Weevil twice (1994 and 2013), recently including information on the National Peanut Festival and on the life and work of Dr. George Washington Carver, the brilliant Tuskegee University researcher who persuasively argued for crop diversification (especially peanut cultivation) in the south.

Finally, it may not be amiss to note that the Boll Weevil is portrayed in regional folk culture in a way that echoes some of Billy’s concerns. One version of “The Boll Weevil Song” has the singer state that “The first time I saw the boll weevil/He was sitting on a square./The next time I saw the boll weevil/He had all his family there./ They were lookin’ for a home,/Just lookin’ for a home.”