Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., is rightly one of the most celebrated Federal District and U.S. Court of Appeals judges in American history. As a member of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama from 1955-1979, Johnson shaped the legal trajectory of several key Civil Rights Movement cases, including Browder v. Gayle (1956), which challenged the segregation of Montgomery’s bus system in the wake of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and Gomillion v. Lightfoot (1961), which challenged the city of Tuskegee’s systemic plan to exclude black voters. In these and numerous other cases, Judge Johnson pioneered judicial methods to address discrimination against African-Americans in education, voting, public transportation, and jury representation. He also ruled in Wyatt v. Stickney (1971), a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case originating in a dispute over Alabama’s Bryce Hospital, which created the basis for minimum standards of care for patients residing in mental health facilities. Judge Johnson was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in 1979, and then to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit after the Fifth Circuit split in 1981, where he served until his retirement in 1999.

Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., is rightly one of the most celebrated Federal District and U.S. Court of Appeals judges in American history. As a member of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama from 1955-1979, Johnson shaped the legal trajectory of several key Civil Rights Movement cases, including Browder v. Gayle (1956), which challenged the segregation of Montgomery’s bus system in the wake of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and Gomillion v. Lightfoot (1961), which challenged the city of Tuskegee’s systemic plan to exclude black voters. In these and numerous other cases, Judge Johnson pioneered judicial methods to address discrimination against African-Americans in education, voting, public transportation, and jury representation. He also ruled in Wyatt v. Stickney (1971), a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case originating in a dispute over Alabama’s Bryce Hospital, which created the basis for minimum standards of care for patients residing in mental health facilities. Judge Johnson was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in 1979, and then to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit after the Fifth Circuit split in 1981, where he served until his retirement in 1999.

Recently, Judge Johnson was portrayed in the 2014 film Selma, in which he is played by Martin Sheen. The film briefly dramatizes a few scenes in Judge Johnson’s Montgomery courtroom in which he approved a petition from various civil rights groups including the SCLC and SNCC, to let the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery March go forward.

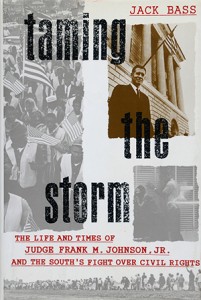

Jack Bass’ Taming the Storm: The Life and Times of Frank M. Johnson, Jr. and the South’s Fight over Civil Rights traces Judge Johnson’s life from his birthplace in Haleyville, Alabama, through his years as a law student at the University of Alabama, his early law practice, and his monumental achievements as a federal judge. Bass illuminates how Johnson’s approach to legal struggles over African-American civil rights came to be so innovative, particularly in his use of judicial powers to fashion equitable relief for racial discrimination. Bass also explores Johnson’s family history and upbringing in Winston County, Alabama, in order to show how and why Johnson came to defy the white South’s commitment to racial segregation.

Before the Civil War, Winston County’s predominately white population mostly worked on small family farms without slaves. The county’s residents had little interest in going to war to preserve slavery, and their representatives in Montgomery voted against secession. Many from the county, including some of Johnson’s ancestors, served in the Union Army. Partly due to this legacy, Johnson’s father belonged to the Republican Party, which in the early twentieth century was still the “party of Lincoln” to the rest of Alabama and the solidly Democratic South. Johnson’s father held a longtime patronage post as postmaster in Haleyville, and later became a probate judge, one of the few Republicans to hold office in Alabama at the time. Johnson’s political background and early life experiences led him to develop the courage, moral fortitude, and convictions that led to his dedication to upholding the law despite threats of violence and the social and political opposition of his peers.

Bass relies heavily on a wealth of primary material, including several years’ worth of interviews with the judge himself, as well as extensive interviews with Judge Johnson’s wife, Ruth, and many of his friends, colleagues, and law clerks. While this approach provides an excellent depiction of Johnson’s immediate personal and professional life, its focus limits the book to the perspective of privileged white professionals. Considering the direct impact that Johnson’s work had on the South’s African-American communities in their fight for civil rights, including voices beyond those that knew Johnson personally might have broadened the book’s depiction of his legacy and provided a more critical perspective on his work.

Bass’ work should be of use to those interested in learning more about Johnson’s life and his significant influence on legal history in both Alabama and also the United States as a whole. Scholars should also seek out Volume 109 of the Yale Law Journal, which was dedicated to celebrating Johnson’s legacy and published shortly after his death. It includes encomiums from John Lewis, a civil rights leader and longtime member of the U.S. House of Representatives; Judge Myron Thompson, Johnson’s replacement in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama; and Ronald Krotoszynski, professor at the University of Alabama’s School of Law and one of Judge Johnson’s former law clerks. Additionally, the Alabama Law Review recently hosted a symposium on the 50th Anniversary of the passage of the Voting Rights Act, including an address from Jack Bass. A forthcoming issue of the review will print some of the papers given at the symposium.