The following is a post which discusses the history of the University of Alabama School of Law. It covers incidents, developments, and personalities concerning the deanship of Albert Farrah, which began in 1913. This post is the second in a series designed to carry us through the highlights of 150 years of Law School history. In this series we shall employ several authors, who will focus on either chronological or topical approaches to the issues at hand.

A.J. FARRAH, FROM MICHIGAN TO ALABAMA

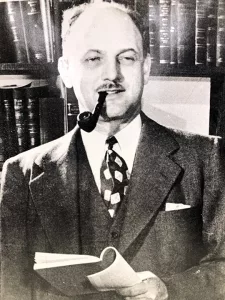

Dean Albert J. Farrah was born in Adrian, Michigan in 1863, and died in Tuscaloosa in 1944, a few days short of his eighty-first birthday. He received his education at Adrian College and at Cornell College in Iowa, after which he taught school and was Superintendent of Schools at Michigamme, Michigan. In the meantime he studied law at the University of Michigan. He received his LLB from Michigan in 1896 and practiced in Ann Arbor for several years while teaching at the University of Michigan as an instructor.[1]

In 1900 Farrah embraced an opportunity to move south to Deland, Florida, where he was the founding dean of the Stetson University School of Law. In 1909, “he was called to the University of Florida, where he again founded the school and became Dean and Professor of Law.”[2] There is no doubt that Farrah’s teaching style was challenging, probably in the best Socratic fashion. The editors of Stetson’s 1909 yearbook, the Orange Thorn, quoted him as having warned his senior class that “the law is a jealous mistress”—an old saw worked to death by most law professors of the time. Farrah, however, apparently meant what he said. Speaking of the senior class, the editors observed that “of all those who have paid court only three have proved sufficiently faithful to satisfy her jealous demands and present themselves as candidates for her reward, . . . duly approved by her lawfully constituted agent, A.J. Farrah.”[3]

In 1912 the University of Alabama’s president, George H. Denny, invited Farrah to come to Tuscaloosa as a law professor. A year later the law dean William Bacon Oliver resigned to run for congress and Farrah was named dean of the law school. The two men, Denny and Farrah, would work together for much of the following three decades. It was a productive arrangement, for both men shared the common goal of making Alabama one of the best schools in the south.[4]

STUDENTS, FACULTY, AND CAVEATS: EARLY YEARS, 1913-1920

One measure of Farrah’s success was the continued growth of law school enrollment. From 139 students in his first year as a professor the number of law students rose to 277 in the academic years 1934-1935.[5] Farrah, however, was concerned about more than rising numbers; his focus was also about law students as individuals. He remarked, long after the fact, that the “friendship and support” of his students was crucial to his success in “that hard first year of service” and afterward.[6] Given this closeness to the students it should be no surprise that Farrah’s emphasis was not just about developing “sheer intellectual brilliance.” His colleague and successor William Hepburn wrote that Farrah “wanted the Law School to produce its share” of great intellects; but he was “just as interested in the average student, even the poor student,” and “nothing “delighted him more than to discover that some student he had at one time contemplated dropping from school for poor work had made a success at the bar.” Hepburn noted that Farrah also concerned himself with “standards of ethical practice, and he gave much thought to questions of legal ethics.”[7]

Farrah was an excellent classroom teacher—though, as the 1916 Corolla put it, his use of the Socratic Method made him “the terror of those unfortunates who happen to be unprepared.”[8] Still, his students saw him as more than just an academician. In dedicating the 1917 Corolla to Farrah, its editors remarked upon his “faithful service,” his “ability as an instructor and his high character as a man.”[9]

There is no doubt that Farrah was something of a wonder-worker at the School of Law, but we should remember that the times in which he lived imposed considerable limitations upon his larger impact. By a combination of law and custom, two large demographic groups were drastically underrepresented at the School of Law. The school had admitted two female students prior to Farrah’s arrival: Luelle Lamar Allen, who graduated in 1907, and Maud McLure Kelly, Class of 1908.

Indeed Kelly, who had graduated third in her class, was already a successful practitioner by the time Farrah came to Tuscaloosa.[10] But Farrah did not profit by considering her example. Female students studied law during his deanship in ones and twos.

Even more rigidly, Alabama schools and colleges were segregated by race during Farrah’s entire tenure (and for decades before and after). African-American school children were prohibited by law from studying alongside white children, and while the laws governing college students were much less specific—the 1907 Code contains no reference to race in the laws pertaining to the University of Alabama—still the custom of exclusion was firmly in place.[11] For much of the first half of the twentieth century, the state offered no professional legal education for African Americans.[12] Thus Farrah, like nearly all white educators, played his part in a situation little removed from what one scholar has called the “nadir” of American race relations.[13]

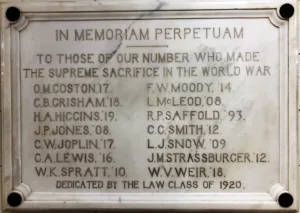

When Farrah took over the deanship, the Law School had one other professor, Adrian S. Van de Graaff, and “two part-time lecturers.” Farrah quickly added another full-time faculty member, Edmund C. Dickenson, whom he had known at the University of Florida. The law faculty was in a state of flux during the late 1910s and early 1920s—the World War and its aftermath were largely to blame.

But by the mid-1920s Farrah presided over a faculty of five full-time law professors and a part-time staff that featured a future Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court.[14]

STUDIES, PUBLICATIONS, AND ACCREDITATION, 1920-1928

As early as 1920-1921, Farrah and President Denny worked successfully to persuade the University’s Board of Trustees to approve a three-year course of study, bringing the Law School up to what was increasingly the national norm. This move “permitted expansion of existing courses, particularly Property, Torts, and Equity, and the addition of new ones, including Practice Court and several electives.” These courses were taught by the “case-study technique,” which required students to use casebooks and brought them under the Socratic gaze of their professors. The 1920s also saw the launch of the school’s first scholarly journal. After some time spent in planning, the Alabama Law Journal was first issued in October 1925, edited by a panel of faculty members. The decade also saw the beginnings of national legal fraternities and other law-related clubs at Alabama, including the Somerville Literary Society, founded in 1924.[15]

By the 1920s, University of Alabama law graduates were making a name for themselves, which was reflected in the state legislature’s 1923 renewal of the “diploma privilege”; this allowed UA Law graduates admission to the bar without sitting for a bar exam.[16] In the meantime, Farrah pursued the goal of American Bar Association membership. By 1922, the ABA had required its members to maintain a three-year program of instruction—already in operation at Alabama—and had mandated that its members require two years of college as a necessary preliminary to law school admission. At the urging of Denny (and Farrah), the UA Trustees approved the new admissions standard in 1926. Clearing this second hurdle was sufficient, and in 1926 the ABA placed the law school on its list of approved law schools. After two years’ probationary membership, the Law School was accepted into membership in the Association of American Law Schools, the legal academy’s highest degree of accreditation.[17]

THE CROWN JEWEL

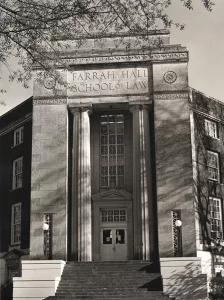

To Farrah, the only missing element of the Law School was a proper setting. Since the beginning of his tenure, the school had been housed in Morgan Hall, an attractive, recently constructed building; but it was but hot in the summer, cold in the winter,[18] and generally cramped.[19] President Denny agreed with Farrah, and starting in 1920 he made construction of a new law school building a priority project.

By 1925 the University was able to allocate $105,000 for construction of such a building; that year a public campaign was announced to raise an additional $25,000. Farrah toured the state “raising funds from alumni and friends,” as did a number of practicing lawyers. These efforts raised $35,000 for the new structure—a building that was to be named Farrah Hall.[20]

The new structure, dedicated on October 29, 1927, was designed to serve approximately 200 students. Constructed of “brick and stone,” it was three floors tall. The first floor contained a locker room, class rooms, club rooms, a “men’s smoking room,” storage rooms, and the inevitable furnace room. Rooms on the second floor included an assembly room, a large classroom, the “practice court” room, the office of the clerk of the practice court and the chambers of the judge of the practice court. The third floor—the heart of the building—housed the library, with its reading room, its “stock room” (i.e., stacks) filled with some 8,500 volumes, and a mezzanine level whose windows would help to insure good lighting. In addition the third floor was the site of the dean’s office, the librarian’s office, faculty offices and rooms given over to the Alabama Law Journal.[21]

A committee headed by Tuscaloosa attorney and part-time law professor Ed Livingston coordinated the Farrah Hall dedication ceremonies, with contributions from Dr. Denny, representatives of the local and state bars, various judges, and Governor Bibb Graves. The occasion began with the singing of “America” and with a pious invocation.

The speeches were six in number, including a “Dedicatory Address” by Birmingham attorney Henry Upton Sims, who urged that “the ideal of the profession of the law should be to find the true principles of legal rights and wrongs, and to establish them, rather than merely to become skillful and successful in winning cases.” Sims praised the current national campaign to generate a “restatement” of law; and he urged Farrah and his faculty and students to conduct researches into the nature of law. Any good law school, Sims maintained, should offer course in jurisprudence, legal philosophy, and legal history. [22] This vision of legal education—which Sims felt should be made available to undergraduate and graduate students as well as law students—has been largely realized today

The University was brim-full of optimism concerning its Law School. The Corolla of 1928-1929 stated that whatever the school’s past accomplishments, “the future may justly expect much more from it because of its new building and equipment”—then predicted that “The School of Law will meet these just expectations.”[23]

HARD TIMES

The autumn of following year brought with it the onset of the Great Depression, the effects of which lingered in the United States’ and Alabama’s economy for most of the following decade. The initial effect on the law school, however, was oddly positive—since “Loss of economic opportunity for young people brought increased numbers of students to Farrah’s doors.”

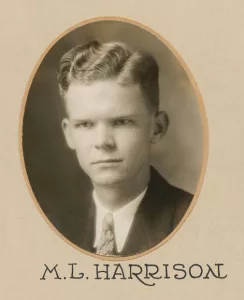

Enrollments increased from 117 students in 1928-1929 to 277 in 1934-1935, as young Alabamians sought to weather the storm. At the same time, state budget constraints were such that Farrah could not expand his faculty; but in the course of retirements and departures, Alabama gained two young professors who would serve, successively, as deans of the law school: William M. Hepburn (dean, 1944-1950) and M. Leigh Harrison (dean, 1950-1966).[24]

The troubled decade of the 1930s was a time when a number of Farrah’s former pupils were of an age to run for political office. The Dean maintained a considerable interest in these races. His friend William Hepburn described Farrah’s attitude when one of his graduates ran against another. “He would enumerate the best qualities of X, and say, ‘Well I cannot possibly vote against him.’ Then he would enumerate the best qualities of Y and say the same thing about him.”[25] At roughly the same time, the 1937 Corolla observed that “The high degree of training” provided by the Law School “is evidenced by the large number of alumni who are leaders in the local and national life.”[26]

However much he may have taken an interest in politics, Dean Farrah tried to keep from taking overt political stands. Privately, he was a states-right Democrat—had been one since before he left Michigan—and as such, in these latter years, he occasionally gave voice to mild criticisms of the New Deal and the advance of federal power.[27] Some causes, however, transcend issues of politics and propriety. Such was the case with the controversies surrounding the nine “Scottsboro Boys.” These were African-American youths twice sentenced to death in grossly unfair trials, commencing in 1931. In 1936, Farrah joined with other prominent Alabamians in joining the “Alabama Scottsboro Fair Trial Committee,” which represented one of the state’s better reactions to a sad chapter in its history.[28]

Farrah’s students were not bothered by his politics. In 1937, the law school rewarded academic excellence among its students and recognized Dean Farrah’s achievements by endorsing the creation of the Farrah Order of Jurisprudence. This organization was founded by a law student, John J. Smith, with the intention of “working toward the establishment of a chapter of the Order of the Coif,” at the same time “promoting public respect for the law and the American judicial system.”[29]

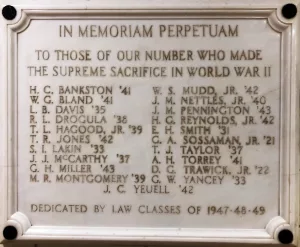

The onset of the Second World War brought about marked declines in law school enrollment, which fell to an alarming low of 18 in the year 1943-1944.

Dean Farrah did his best to cope with the vicissitudes of working with draft-eligible students (and in some cases, faculty), but his health was declining as he approached his eightieth year. Robert McKenzie reports that “In the winter and early spring of 1943 he was critically ill, but by May he was back at his post.” After that he had one more full year as Dean before retiring in June 1944. Dean Farrah died on the 29th of that month.[30]

A week later, Dean William Hepburn, Farrah’s replacement, spoke before the Alabama State Bar Association about his predecessor. He described Dean Farrah as one who had nurtured the School of Law “so that it became in many ways one of the best law schools in the South.” Hepburn spoke of Farrah’s administrative skills and his knack for recruiting both students and faculty, adding that “he was a noted teacher of contracts, constitutional law and common law pleading.” Dean Hepburn believed, in fact, that Farrah’s “influence in the classroom at least equaled, and perhaps exceeded, his influence as Dean of the Law School.”[31]

Trying to characterize Farrah’s “ideals, and the beliefs, and the traditions around which they grew,” Hepburn argued that Dean Farrah was first and foremost “an old-fashioned liberal,” which he declared was “the most difficult of all intellectual positions to maintain.” “It is the point of view,” Hepburn continued, “of the individualist, the man who refuses to be pushed around; the point of view of the man who believes that justice is individualized; and [that] it is of no consequence unless it is individualized so that each person is important in its administration.” So Hepburn and the state bar said goodbye to their Dean, their “leader for a long generation in the life of the state.”[32]

It has been the good fortune of the University of Alabama School of Law to be “reborn,” or more accurately, rejuvenated, on several occasions. More than a decade after B.F. Porter’s failed attempt in 1845, Wade Keyes began a new Montgomery-based UA Law School chartered by the state legislature. A decade after the Civil War swept Keyes’ work away, Henderson Somerville refounded the school in a form that would last for forty years. In 1913 Farrah began his great task at the University of Alabama—bringing legal education in this state into the twentieth century. Over the years he amply succeeded in this endeavor, and the forms and patterns of his success would last for decades.[33]

PMP

[1] See Dean William M. Hepburn, “Address: The University of Alabama Law School,” 67 Alabama State Bar Association Proceedings” 38-44 (1944), at 41-42.

[2] Ibid., 42.

[3] Stetson University Orange Thorn (1909), 47. Ibid., 48, states that the Law Department’s Junior Class “has been so thoroughly and completely overwhelmed and conquered by the study of law.”

[4] Hepburn, op. cit., 42; and Suzanne Rau Wolfe, The University of Alabama: A Pictorial History (University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1983), 128-129, 144.

[5] Hepburn, op. cit., 42-43.

[6] Albert John Farrah, “An Address to the Alabama Bar, 1937,” in Albert John Farrah, 1863-1944: Addresses, Papers and Letters (reprint; Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Law School Foundation, [1985]), 52-54, at 53.

[7] Hepburn, op. cit., 44.

[8] 1916 Corolla, 24. Ibid., 333, contained a parody by 1916 class member W.B. Dortch of Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Danny Deever.” The refrain of the parody was “they’re bustin’ SENIOR LAWYERS in the mornin’.” Ibid., 374 contains a cartoon portrait titled “Dean Farrah tries out for Glee Club.”

[9] 1917 Corolla, [6].

[10] Paul McWhorter Pruitt, Jr., “Maud McLure Kelly” (2008) Encyclopedia of Alabama (online).

[11] 1907 Code of Alabama §1757, §§ 1949-1951. For the politics behind the creation of a “State Normal School and University for Colored Teachers and Students,” see Horace Mann Bond, Negro Education in Alabama: A Study in Cotton and Steel (1969; Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994), 107-110. For one white editor’s racist response to the prospect of integrating the University of Alabama, see G. Ward Hubbs, Searching for Freedom after the Civil War: Klansman, Carpetbagger, Scalawag, and Freedman (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2015), 151-153.

[12] By the late 1940s the state of Alabama offered African American applicants to law or medical schools a strange bargain. By statute, the state offered them generous support, virtually a “full ride,” to attend out-of-state schools. Of course offering such assistance was a tacit admission that there were young black Alabamians fully qualified to attend such schools. Perhaps it was for this reason that the codifiers hid the enabling legislation away in a 1955 Cumulative Supplement [pocket part to Volume 8] of the 1940 Alabama Code §40 (1). The provision was finally codified in the 1958 Recompiled” Code of 1940; see Ala. Code §52-40(1) (1958).

[13] Rayford Logan, The Negro in American Life and Thought: The Nadir, 1877-1901 (New York: The Dial Press, 1954).

[14] Robert H. McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future: The First One Hundred Years of the University of Alabama Law School, 1872-1972,” 25 Alabama Law Review 121 (1972), at 135-136. The future Supreme Court justice was J. Edwin Livingston (1892-1971), who taught part-time at the Law School from 1921 to 1940. He served as an associate justice on the state’s Supreme Court from 1840 to 1951, and as chief justice form 1951 to 1971. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Ed_Livingston#:~:text=Edwin%20Livingston%20(March%2017%2C%201892,was%20born%20in%20Notasulga%2C%20Alabama.

[15] McKenzie, op. cit., 137-138, quoted passage at 137. See also The Corolla 1924 [Vol. XXXI], 134-142.

[16]McKenzie, op. cit., 139; and Pruitt, “Life and Times of Legal Education in Alabama: 1819-1897: Bar Admissions, Law Schools, and the Profession,” 49 Alabama Law Review 309 (1997).

[17] McKenzie, op. cit., 139.

[18] See Paul M. Pruitt, Jr. and Penny Calhoun Gibson, “John Payne’s Dream: A Brief History of the University of Alabama School of Law Library,” 15 Journal of the Legal Profession 6 (1990-1991).

[19] McKenzie, op. cit., 140 n.73.

[20] Ibid., 139-140. For somewhat different figures ($75,000 from the University and $40,000 from the fund-raising campaign) see “Same Letter Sent to Many Subscribers” in Albert John Farrah, 1863-1944: Addresses, Papers, and Letters, 65.

[21] “Banquet Given for Dean Farrah by His old Florida State and Stetson Students,” originally from the Crimson White, reprinted in Albert John Farrah, 1863-1944: Addresses, Papers, and Letters, 86. As for the library, the 1920s was a time when, as historian Robert H. McKenzie put it, “the University increased its support of the [law] library somewhat, and by 1928 some 9.500 volumes had been accumulated.” See McKenzie, op. cit., 140.

[22] Henry Upton Sims, “A Vision of Broader Usefulness for Law Schools,” 3 Alabama Law Journal 85, 90, 91-92, 94-95 (1928).

[23] 1929 Corolla: A Yearbook of the University of Alabama, volume 36 (1929).

[24] McKenzie, op. cit., 140-141. In spite of many moves and shifts, the law faculty stayed constant at seven members for most of the 1930s.

[25] Supra n. 1, at 44.

[26] 1937 Corolla, 64. These alumni included judges, governors, legislators, congressmen, and senators. In the 1930s alone, Benjamin Meeks Miller (class of 1888) served as governor, Hugo L. Black (class of 1906) was a U.S. Senator and U.S. Supreme Court justice, J. Lister Hill (class of 1915) was a U.S. Congressman and U.S. Senator, and John C. Anderson (class of 1883) was chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court. See University of Alabama Law School Directory of Graduates, 1872-1970 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Law School Foundation, 1970), alphabetical listings.

[27] Albert John Farrah, 1863-1944: Addresses, Papers, and Letters, 57-58 (citing to “A Radio Address Following Nine Students of Law School,”), 91-92.

[28] For the cluster of injustices that was “Scottsboro,” see Dan T. Carter, Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969), 356 and passim.

[29] McKenzie, op. cit., 142.

[30] McKenzie, op. cit., 142-143; and 6 Alabama Lawyer 93 (1945).

[31] Supra n. 1, at 41, 43.

[32] Ibid., 44.

[33] For a useful survey of Farrah’s careers see William H. Pryor, Jr., “The Legacy of Albert Farrah,” Alabama Lawyer, 72 (2011), 211-216.