The following is a post which discusses the early history of the University of Alabama School of Law. It covers incidents, developments, and personalities dating from the 1840s, which saw the earliest efforts to found the school, until the deanship of Albert Farrah, which began in 1913. This post is the first in a series designed to carry us through the highlights of 150 years of Law School history. In this series we shall employ several authors, who will focus on either chronological or topical approaches to the issues at hand.

EARLY FOUNDATIONS AND FORMATIVE YEARS

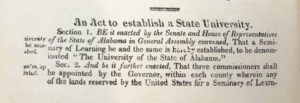

Consistent with other new territories and states which were emerging during the early nineteenth century, supporters of Alabama realized the importance of establishing an institution of higher education to strengthen the transition from a frontier environment to that of a productive society. On April 20, 1818, the United States Congress approved an act that reserved an entire township in the Alabama Territory “for the support of a seminary of learning.”[1] Almost one year later on March 2, 1819, the Enabling Act for the admission of Alabama to the Union provided for a second township to be added to the land grant to support the institution.[2] By 1820, the General Assembly of the state of Alabama passed “An Act to Establish a State University,” however, the new institution would exist only on paper until it opened its doors at Tuscaloosa eleven years later on April 12, 1831. The new university was charged with the “promotion of the arts, literature, and sciences.”[3] Early course offerings between 1831 and 1845 consisted of: Moral and Mental Philosophy, Ancient Languages, Mathematics, Chemistry and Natural History, English Literature, Mineralogy and Geology, and Astronomy.[4]

The new university was charged with the “promotion of the arts, literature, and sciences.”[3] Early course offerings between 1831 and 1845 consisted of: Moral and Mental Philosophy, Ancient Languages, Mathematics, Chemistry and Natural History, English Literature, Mineralogy and Geology, and Astronomy.[4]

Well into the early nineteenth century, the study of law was typically pursued through the practice of traditional law office apprenticeships. Young men aspiring to practice law as a profession were chosen by judges, or well-established and respected senior lawyers, to “read law” in their offices or chambers. Through the study of select cases, and legal works such as those of William Blackstone and Edward Coke, an apprentice would absorb the required knowledge to pass examination sufficient to be admitted to the bar. The first law schools in the United States were inspired by these law apprenticeships and employed many of the same techniques.[5]

Throughout the nineteenth century, the study of law moved from apprenticeships to the college and university systems that developed throughout the century.[6] By the early 1820s private law schools, which were the first institutions to offer serious professional training, were being absorbed into college and university systems providing prestige as well as the ability to grant degrees.[7] For colleges and universities, this strategy offered the benefit of adding an already established legal training program to their curriculum.[8]

By 1843, trustees at the University of Alabama began examining the idea of adding professional schools to the university. In addition to the notion of adding a medical school to the professional curriculum being considered, university trustees were enthusiastically planning a law school.

The trustees met in December 1845 to establish the guidelines for the new law school, and during the winter of 1845-1846 announced in the university catalogue the appointment of a prominent legal authority and fellow trustee Benjamin F. Porter as the first professor of law.

Unfortunately, Porter’s ambitious plans for the two-year law degree at Alabama were never realized. University trustees had imposed harsh regulations for the law school that assured its secondary status to the regular faculty and university. Restrictions such as prohibiting university students from attending law lectures, not allowing law lectures to be given on the university premises, as well as matters of discipline in which regular university faculty had authority over law students including the power of expulsion were overly restrictive. Furthermore, law students were not allowed access to the university dining hall or university housing. Funding in support of the law program was also problematic. The law professor’s salary was determined by student fees and no university funding was to be used to support the law school. The law school faculty was restricted to a single professor of law who was required to confer with state supreme court judges in planning lectures and selecting textbooks. The university trustees and faculty had imposed regulations and restrictions on the law program which contributed to its failure. As the result, no students registered for classes and the law program foundered.[9]

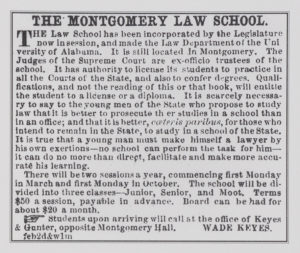

The second attempt to establish a law department within the University of Alabama reflected the earlier pattern of universities such as Yale in 1824, Harvard in 1829, the University of North Carolina in 1845, and Tulane in 1847, all of which absorbed existing private professional legal training into the university structure.[10] On January 25, 1860, the Montgomery Law School was designated as the “Law Department of the University of the State.”[11] The law school evolved from a series of lectures developed by chancellor of the southern division of Alabama, Wade Keyes.[12]  Born in Limestone County, Alabama in 1821, Keyes studied at LaGrange College, the University of Virginia, and graduated from the law department at Transylvania University at Lexington Kentucky. After extensive travels, Keyes returned to Alabama and soon established himself in the Alabama legal community.[13] He began teaching classes on property law at Montgomery and soon after, the Montgomery Law School developed as an expansion of those lectures.[14]

Born in Limestone County, Alabama in 1821, Keyes studied at LaGrange College, the University of Virginia, and graduated from the law department at Transylvania University at Lexington Kentucky. After extensive travels, Keyes returned to Alabama and soon established himself in the Alabama legal community.[13] He began teaching classes on property law at Montgomery and soon after, the Montgomery Law School developed as an expansion of those lectures.[14]

The state legislature appointed its state supreme court justices as ex officio trustees of the school with the power to assign professorships, create by-laws, and control the real and personal property of the school.[15] Although the school was designated as the Law Department of the University of the State, mutually protective language within the act allowed either the trustees of the University of Alabama, or the Montgomery Law School to dissolve the connection between the two institutions.[16] Very likely this protective agreement was influenced by the earlier administrative failures of the university’s attempt to establish a law program in 1846.

The Montgomery Law School offered students full use of the state and supreme court libraries and classes were conducted within the state capitol.[17]

The curriculum was divided into three levels that included Junior, Senior, and Moot with tuition assessed at fifty dollars for each session. There were two sessions per year, beginning the first Monday in March and the first Monday in October.[18] The law school was authorized to confer degrees and to license students to practice in Alabama’s court system. Additionally, diplomas were awarded based on subjective evaluation of the student’s performance which represented a significant break from the law office apprenticeships that allowed a student to practice law on the completion of a set of quantitative, and often minimum requirements.[19] On this point Keyes noted, “it is scarcely necessary to say to the young men of the State who propose to study law that it is better, caeteris paribus [all things being equal], for those who intend to remain in the State, to study in a school of the State.”[20] Beginning its operations in March 1860, the Montgomery Law School completed two sessions ending in February 1861.

The literal drumbeat of war overshadowed Keyes’ short-lived law school as Alabama had seceded from the Union the previous month and was preparing for war. Although the law school was well organized, administratively sound, had scholarly leadership and good resources, it was not enough to sustain the school through the turbulent and destructive years of the Civil War.[21]

Following the burning of the university by federal troops on April 4, 1865, the University of Alabama struggled to reopen in the challenging postwar world. Eventually the university reopened during the 1871-1872 academic year, although only ten students enrolled, four of them sons of faculty members. In a difficult environment which was amplified by Reconstruction-era political concerns, the university attempted to balance the demands of institutional viability and its desire to provide a faculty free of political influence with mixed success.[22] However, it was during this period that the permanent establishment of the law school was finally realized in February 1872 with the admission of four students; an additional two students were admitted in October. University president Nathaniel Lupton acknowledged the establishment of the law school to the regents, reporting “With proper encouragement on the part of the Regents and the same liberal policy heretofore extended by the faculty I am led to believe that the law department is no longer a mere experiment, but a permanent feature of the University.”[23]

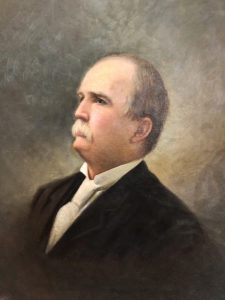

From 1872, the school of law was indeed a permanent part of the university and welcomed its first professor of law, Henderson M. Somerville who became known as the “Founder of the Law School.”[24] After graduating from the University of Alabama (A.B. in 1856 and A.M. in 1859), Somerville earned his law degree in 1859 from Cumberland Law School in Tennessee and practiced law in Memphis. He returned to Tuscaloosa during the war in 1862 to teach mathematics at the university. After the university was forced to close in 1865, he practiced law in Tuscaloosa until his appointment as law professor by the Board of Regents in 1872. In addition to his service to the law school, Somerville served as an Alabama Supreme Court Justice from 1880 to 1890, and eventually resigned from his position at the law school following his appointment by President Benjamin Harrison in 1890 to a chairman’s position within the United States Customs Service.[25]

As the sole law professor during his first two academic years, Somerville offered lectures and recitations drawing from texts which included, Walker’s Introduction to American Law, Kent’s Commentaries on American Law, Stephen’s Principles of Pleading, Greenleaf’s Treatise on the Law of Evidence, Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, Roscoe’s Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases, and predictably, the Revised Code of Alabama. Additional readings were “encouraged when the student has the requisite time.”[26] Somerville’s course of study was designed to be completed in three, four-and-one-half month terms or a combined eighteen months. It consisted of a combination of lectures, assignments from texts, and moot courts—which relied on assistance from local attorneys. There was no prerequisite for admission, and— reminiscent of the funding strategy from the failed attempt in 1846— student tuition provided the only means for Somerville’s salary. The separation of the law school’s budget from the university’s main “Academic Department” supports the notion that the university expected law professors’ compensation to come from a combination of their private practice and classroom service. By the 1880s, the law school had established the custom of leaning on its own graduates for faculty appointments, including Somerville’s son Ormond in 1896.[27]

Despite the early challenges that Somerville faced in his first few years leading the law program, his leadership produced a successful program by 1874 that graduated nine students who had completed the course of study passing both written and oral examinations. His early success prompted the regents in July 1875 to expand the program including the appointment of additional faculty member John Mason Martin who was hired as professor of equity jurisprudence.[28] Within the year, the university offered further support to the law program by establishing annual salaries of $500 to Somerville and Martin plus the tuition fees that were capped at $25 per session.[29] In addition to the regents’ recognition of the law school’s potential demonstrated by Martin’s appointment and salary support for the faculty, in 1876 the Alabama Supreme Court provided that certified graduates of the law school would be admitted to the Alabama bar and licensed “to practice law in any court of the State of Alabama” without an examination.[30]

With Somerville’s successful beginning, the law school’s enrollment averaged more than fifteen students per year for the next two decades. It was clear to the university administration that the sustained growth required the expansion of the faculty; however, with limited funding the trustees addressed the shortage by enlisting university presidents as teachers as well as the expanded use of local attorneys as part-time instructors.[31] Between 1880 and 1897, all three university presidents—Burwell B. Lewis (1880-1885), Henry D. Clayton (1886-1980), and Richard C. Jones (1890-1897)—were respected attorneys who taught classes in international and constitutional law.[32]

The use of university-connected regular faculty as well as local attorneys as part-time instructors provided a convenient and frugal means to satisfy the early law school’s teaching demands; however, by the 1880s the practice had created a teaching faculty that were often drawn away from the law school by their political aspirations. In 1885, John Mason Martin who had previously served in the Alabama state senate from 1871-1876, was elected to the United States House of Representatives. University trustees encouraged him to maintain his connection to the law school, however, he eventually returned to private practice in Birmingham after serving one term in Congress.[33] Tuscaloosa attorney and state legislator Andrew C. Hargrove was appointed lecturer in equity jurisprudence on Mason’s departure, and was eventually promoted to professor of equity jurisprudence from 1888 until his death in 1895.[34]

Continuing the practice of hiring from within the community, Alabama graduate, practicing attorney, and former UA Trustee, John D. Weeden joined the faculty in 1885 as lecturer in statute and common law. Indeed, even Henderson Somerville reduced his responsibilities at the law school to devote more time to his duties following his appointment in 1880 as a justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, trading his title of professor in 1887 for lecturer in statute and common law until his departure from the faculty in 1890.[35]

Drawing on its own graduates for faculty positions continued after Somerville’s departure with the appointment of Tuscaloosa attorney and UA law class of 1884 graduate Adrian S. Van de Graaff to the position of Professor of Statute and Common Law in 1891. Additionally, Van de Graaff had married professor Hargrove’s daughter Minnie Cherokee Hargrove the year before joining the faculty.[36] With Hargrove’s departure from the law school, Van de Graaff transitioned to professor of equity jurisprudence and the practice of hiring from within came full circle with the appointment in 1896 of Henderson Somerville’s son, Ormond Somerville, in the position that his father previously held as Professor of Statute and Common Law.[37]

Throughout Henderson Somerville’s tenure, administratively the law school was loosely structured resulting from the early challenges of a developing program, combined with Somerville’s frequent absences as the product of his supreme court responsibilities. From the beginning, the relationship between the law school and the university administration was often unclear. As early as 1875, the university regents asserted direct control over the administrative functions of the law school through the appointment of university president Carlos Smith as “Chancellor” of the law school. However, Smith did not have a law degree and the title had little functional meaning for the law school.[38] By the 1880s as the result of the university trustees’ increasing interest in the law school, they moved to assert more direct control over the law school. University president Burwell Lewis had served on the law faculty; however, with the administration of Henry D. Clayton the lines of authority were redefined. Clayton was made Chancellor of the law faculty and law students were subject to the same rules and discipline as other university students. The establishment of the president’s authority over the law school streamlined the school’s administration and weakened its independence; yet, it also allowed for improvements to the curriculum that conformed to instruction at the top national law schools.[39] The desire to compete nationally is demonstrated in a trustee committee proposal in 1886 that stated law instruction should “conform as nearly as practicable to that pursued in the first class Law Schools in the other American States.” With national standards in mind, as early as 1888 the trustees asked the law faculty to revise the legal program to two years, in fact, the establishment of a two-year course of study would not occur until 1897.[40]

In addition to the changes to the course of study, class fees, and the implementation of an honor code under Clayton’s presidency, the trustees realized the importance of establishing a law library. During the 1886-1877 academic year, the trustees approved the withdrawal from the main library “such books of law and literature as were appropriate” for the law library.[41] Additionally, the state legislature passed an act in December 1886 authorizing the supreme court judges “from time to time, to set apart and turn over to the Law Department of the State University copies of such second hand or superseded editions of law books, known as textbooks, as may be deemed necessary.” The legislature also provided for other works such as the Code of Alabama, legislative acts, supreme court reports, Brickell’s Digest and other works to be supplied to the law library.[42] In 1887, university trustees approved a $500 initial book budget and enlisted the services of a law student as librarian. Additional works were acquired through a variety of sources such as a collection of books donated in 1893 by university trustee James E. Webb, Montgomery legal bookseller Joel White, and Alabama Supreme Court Justice George W. Stone. Within four years the collection numbered 1,200 volumes.[43]

During the 1880s and 1890s, trustees’ interest in and support for the law school further increased and in 1894 Professor Van de Graaff assertively argued for the trustees to provide for a salaried dean position consistent with other academic departments within the university. No action was taken until March 1897 when trustee and committee chair Willis G. Clark recommended the law deanship as well as a two-year curriculum for the law program.

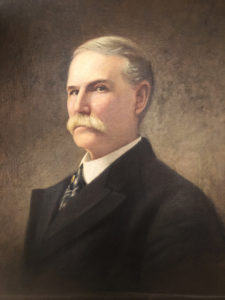

The committee did not look beyond its own membership for candidates and in July they selected William S. Thorington as the law school’s first dean. The newly-selected dean received a salary of $2,500 and a residence with the expectation of a salary increase if the number of law students in the future numbered more than thirty.[44]

The law school’s first two deans, William S. Thorington and William B. Oliver provided a transition between the early development of the law program with its many challenges and the long and transformational tenure of Dean Albert J. Farrah from 1913-1944. The law school was thriving and as its reputation grew, enrollment increased from an average of fifteen students per year from 1877-1897, to an enrollment of more than fifty after 1898.

William Thorington attended the university between 1863 and 1865 but did not complete a degree because of the destruction of the university at the end of the Civil War. He read law under chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, William P. Chilton, and established a law practice in Montgomery, Alabama in 1867.

He was member of Governor Edward A. O’Neal’s staff (1882-1886), Montgomery city attorney and city court judge (1891-1892) and an Alabama supreme court justice in 1892. Additionally, Thorington had served as a University of Alabama trustee for almost twenty years before accepting the appointment as law dean.[45] Throughout Thorington’s tenure, in addition to his responsibilities as dean, he maintained full-time teaching duties. Unfortunately, the increase in students was not accompanied by an increase in teaching faculty. Thorington shared teaching responsibilities with Ormond Somerville and a number of part-time instructors who were recruited from the local legal community.

However, changes in the makeup of the faculty were necessitated with Thorington’s resignation in 1909 following his appointment by the U.S. circuit court as “special master” for the Middle District of Alabama in the railroad rate cases between the state and railroad companies.[46]

With Somerville’s leave of absence on January 1, 1910, William Bacon Oliver was appointed acting dean in 1910 and dean the following year. Both Thorington and Oliver were challenged with heavy teaching loads which is evidenced by the enlistment of seven local attorneys to compensate for Thorington’s course load after his departure. Although they were functioning in a challenging environment, the standards of the law school were raised during the first deans’ tenure and the two-year curriculum was finally implemented in 1897.[47]

First Year

The Law of Persons; Personal Property (including Sales)

Domestic Relations

The Law of Contracts

The Law of Torts

Constitutional and International Law

Mercantile Law

Second Year

The Law of Evidence; Pleading and Practice in Civil Cases

The Law of Corporations

The Law of Real Estate

Equity, Jurisprudence and Procedure

The Law of Crimes and Punishments[48]

Both Thorington and Oliver pressed university leadership to improve the academic standards of the law school; however, entrance requirements remained inconsistent and the workload was frequently irregular.[49] The “textbook and lecture method” of instruction was in place until 1912 when the case method was introduced.

Early instruction focused on the principles of English and American common law with special emphasis on the statutes and specific application of common law in Alabama. Students were advised that it would benefit them to have read Blackstone’s Commentaries before beginning their program.[50]

In addition to the academic challenges that the law program faced, the law school frequently changed physical locations around a campus that was being rebuilt following its destruction at the end of the Civil War.

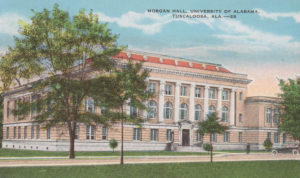

Originally located in Woods Hall in 1872, the law school moved to Manly Hall in 1886 when that building was completed. By 1910, the school was once again uprooted and moved to Barnard Hall where it shared housing with the university gymnasium.

In 1912 the law school was relocated to the third floor of Morgan Hall which had been recently constructed, however, it was not completely furnished and was reportedly cold in the winter and hot during warmer months. For fifteen years, the third-floor accommodations at Morgan Hall housed faculty, librarians, and students.[51] The frequent moves were disruptive and made it difficult for faculty and students to focus on their studies, as well as introducing the challenge of moving the law library every few years.

By 1910, university president John W. Abercrombie led efforts to improve academics at the university. Part of his initiative was directed at improving the law program. With that goal in mind, he lobbied the trustees to enhance the law library, expand the curriculum, and double the teaching faculty to enable the program to be consistent with national trends in legal education. Abercrombie’s recommendations were slow to mature as the result of the president’s resignation in September 1911 followed by Dean Oliver’s resignation in April 1913 to pursue a congressional seat.

While many improvements to the law school were evident by 1912 including the first woman graduate in 1907, the law program would soon enter a transformative period under the leadership of President George H. Denny and Dean Albert J. Farrah. It would be during Dean Farrah’s tenure that the law school would earn a place of respect within the university and upgrade the program to national standards. In Dean Farrah’s speech to the class of 1916, he acknowledged Thorington’s contributions to the law school, writing “Judge Thorington became connected with the Law School in 1897 and for nearly fourteen years he labored for her unceasingly and unselfishly, laying her foundations broad and deep…we must not forget that he was a pioneer in the cause and, like all pioneers, he was hampered by lack of proper equipment and adequate facilities and was beset by difficulties and discouragements that would have overcome a less resolute man.”[52]

David I. Durham

[1] 3 United States Statutes at Large, 466-467.

[2] Alabama Constitution of 1819, § 6.

[3] Acts of Alabama (1820), 4-5. For the early university, see James B. Sellers, History of the University of Alabama (University: University of Alabama Press, 1953), 3-13.

[4] Thomas Waverly Palmer, A Register of the Officers and Students of the University of Alabama, 1831-1901 (Tuscaloosa: Published by the University, 1901).

[5] Lawrence Friedman, A History of American Law (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973), 318-322.

[6] See, Friedman, A History of American Law, 318-322; and Robert Stevens, Law School: Legal Education in America from the 1850s to the 1980s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983). For a comprehensive treatment of early legal education in Alabama, see Paul M. Pruitt, Jr., “The Life and Times of Legal Education in Alabama, 1819-1897: Bar Admissions, Law Schools, and the Profession,” 49 Alabama Law Review (1997).

[7] Stevens, Law School, 5.

[8] Ibid.

[9] James B. Sellers, History of the University of Alabama (University: University of Alabama Press, 1953), 160-161; and Catalogue of Officers and Students of the University of the State of Alabama: 1846 (Tuscaloosa: M.D.J. Slade, 1846).

[10] Stevens, Law School, 5.

[11] For the enabling legislation of the Montgomery Law School see, Acts of Alabama (1860), 342-344. Additionally for Wade Keyes and the Montgomery Law School see, David I. Durham and Paul M. Pruitt, Jr., Wade Keyes’ Introductory Lecture to the Montgomery Law School: Legal Education in Mid-Nineteenth Century Alabama (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama School of Law, 2001).

[12] E. David Haigler, “The First Law Class of the University of Alabama,” The Alabama Lawyer, 40 (1979), 373.

[13] Keyes published the legal volumes, An Essay on the Learning of Remainders, 1852; An Essay on the Learning of Future Interests in Real Property, 1853; and An Essay on the Learning of Partial, and of Future Interests in Chattels Personal, 1853. Recognition for his work on property rights earned him an appointment by the state legislature to the chancellorship of the southern division of Alabama in 1853. Keyes’ appreciation for the common law is demonstrated by his dedication in An Essay on the Learning of Future Interests in Real Property, to “The Students of the Common Law, With the hope that it may somewhat open to them This Difficult Learning Without which no one can attain to the excellence of a Common Lawyer.” See, Wade Keyes’ Introductory Lecture, 3.

[14] Wade Keyes’ Introductory Lecture, 4.

[15] Acts of Alabama (1860), 343 (section 3).

[16] Ibid., 344 (section 10).

[17] Ibid., 343 (section 7).

[18] Wade Keyes’ Introductory Lecture, 4-5. Board was available for twenty dollars per month and a few of the students boarded at Keyes’ home. Also, see an advertisement for the Montgomery Law School, Montgomery Weekly Advertiser, March 7, 1860.

[19] Wade Keyes’ Introductory Lecture, 5.

[20] Haigler, “The First Law Class of the University of Alabama,” 371.

[21] The Supreme Court of Alabama listed five men admitted to the bar in February 1861 and likely represent the only graduating class of the Montgomery Law School. Haigler, “The First Law Class of the University of Alabama,” 374. Following South Carolina (December 20, 1860), Mississippi (January 9, 1861), and Florida (January 10, 1961), Alabama seceded from the Union on January 11, 1861.

[22] Sellers, History of the University of Alabama, 308.

[23] Robert H. McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future: The First One Hundred Years of the University of Alabama Law School, 1872-1972,” 25 Alabama Law Review, (Fall 1972): 124.

[24] Ibid. Influential university president George H. Denny (president, 1912-1936 and interim president, 1941-1942) initially associated Somerville with founder status.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Sellers, History of the University of Alabama, 389.

[27] Ibid., and McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 125. Sellers notes as evidence of the early trend of the university drawing from their own graduates for law faculty, between 1872 and 1901, eleven of the twelve men who taught in the law school were Alabama alumni.

[28] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 125. With the hiring of John Mason Martin, Somerville was made professor of statute and common law. The first nine graduates were: Luther M. Clements, Arthur D. Crawford, Robert Jemison, William C. Jemison, Thomas C. McCorvey, Frank S. Moody, Isaac H. Prince, Sherman Prince, and Thomas H. Watts, Jr.

[29] Ibid., 126.

[30] For the law school’s “diploma privilege” see, Code of Alabama (1876), 156, Rule 16.

[31] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 126, n.13. By 1876, the Board of Regents had been replaced by a separate Board of Trustees appointed by the governor under the Constitution of 1875.

[32] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 126.

[33] Thomas M. Owen, History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, 4 vols. (Chicago: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1921), IV: 1165.

[34] Andrew Coleman Hargrove graduated from the University of Alabama in 1856 and received his LL.B. from Harvard Law School in 1859. He practiced law in Tuscaloosa, was a member of the Constitutional Convention of 1875, a state legislator from 1876-1892, and president of the Alabama Bar Association in 1892. He served as land commissioner for the University of Alabama from 1885-1895, and was a professor of law from 1888 until his death in 1895. See, Owen, History of Alabama, III: 748.

[35] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 127; and Sellers, History of the University of Alabama, 390.

[36] Van de Graaff completed his undergraduate work at Yale before attending law school at the University of Alabama. Sellers, History of the University of Alabama, 390. Van de Graaff also had political ambitions and served as a circuit court judge from 1915-1917 and a state representative from 1918-1922. McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 127, n.19.

[37] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 127-128; and Sellers, History of the University of Alabama, 390. Ormond Somerville would further follow his father’s lead by serving as a justice on the Alabama Supreme Court in 1910 until his death in 1928.

[38] See Pruitt, “The Life and Times of Legal Education in Alabama,” 305-306; McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 128.

[39] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 128.

[40] Pruitt, “The Life and Times of Legal Education in Alabama,” 307; McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 129, 131. The first class to graduate under the new system was in 1899.

[41] Paul M. Pruitt, Jr., Penny Calhoun Gibson, “John Payne’s Dream: A Brief History of the University of Alabama School of Law Library, 1887-1980, With Emphasis Upon Collection-Building,” 15 The Journal of the Legal Profession (1990), 5.

[42] Acts of Alabama (1886-1887), 121-122.

[43] Pruitt, Gibson, “A Brief History of the University of Alabama School of Law Library,” 6; McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 128; and Pruitt, “The Life and Times of Legal Education in Alabama,” 306.

[44] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 129; and Sellers, History of the University of Alabama, 391.

[45] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 130.

[46] Ibid., 130-131. Thorington officially remained on the law faculty until 1911, however, his active role ended with a leave of absence January 1, 1910. Also, see Owen, History of Alabama, IV: 1669.

[47] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 131.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid., 132-133.

[50] M. Leigh Harrison, William M. Hepburn, University of Alabama Report to the Alabama Educational Survey Commission, School of Law (University, Alabama: [School of Law], 1944), 3-4.

[51] McKenzie, “Farrah’s Future,” 133; Pruitt and Gibson, “A Brief History of the University of Alabama School of Law Library,” 6; and “Buildings Housing the University of Alabama School of Law,” Special Collections, Bounds Law Library, “Scrapbook—One Hundredth Anniversary (1972).” Manly Hall was renamed Presidents Hall in 2020, and Morgan Hall was renamed English Building the same year by the university Board of Trustees.

[52] Wythe W. Holt, Jr., “A Short History of Our Deanship,” Alabama Law Review 25, no. 1 (Fall 1972): 165; Albert John Farrah: 1863-1944 Addresses, Papers, and Letters (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Law School Foundation, n.d.), 6.