Hugo Black and the Classics is an exhibit in the University of Alabama School of Law Library’s Hugo Black Study that offers insight into Justice Black’s strong interest in Greek and Roman classical works. The collection shown here represents one component of the more than one thousand volumes of Black’s books held at the Bounds Law Library.

HUGO BLACK AND THE CLASSICS

Hugo Lafayette Black (1886-1971) was a native of Clay County, Alabama, and a 1906 graduate of the University of Alabama School of Law. Elected to the United States Senate in 1926, Black proved to be a reformist senator and leading New Dealer. In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him to the United States Supreme Court.

Confirmed despite a furor over his earlier brief association with the Ku Klux Klan, Black served on the Supreme Court for thirty-four years, promoting the First Amendment, working to make the Bill of Rights applicable to the States, and supporting the landmark civil rights decisions of the Warren Court.

Both as Senator and Justice, Black sought to follow programs of reading and self-education. He found Will Durant’s 1929 article, “One Hundred Best Books,” to be particularly useful. Durant’s vision of history was anchored firmly in the Greek and Roman classics, and the writers of antiquity likewise appealed to Black.

In part this was because Black enjoyed the dignity and measured tone of the classics in translation, but even more because he viewed human nature as essentially unchanging. To his mind, the historians and philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome had set forth many observations perfectly applicable to mid-twentieth century America. Daniel J. Meador, who was a Supreme Court clerk for Justice Black in 1954, later commented on Black’s interest in the classics in Mr. Justice Black and His Books (1974), “If there is any single book out of the hundreds he owned which might be said to have been the favorite, it is Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way…. Law clerks over a span of many years recall having The Greek Way recommended by Black in their initial interview with him, or in the early days of the clerkship…. More than any other single book, The Greek Way is essential reading for anyone attempting to understand the mind of Justice Black.”

In his quest for the classics, Black frequented the various out-of-print bookshops of the Washington, D.C. area. He was also a dedicated reader of dealers’ catalogues. Preferring older editions, he assembled a collection of more than forty volumes on the classics.

Numerous volumes contain Black’s annotations and underlined passages. These books, many of which reflect the height of Victorian classical scholarship, can be considered the cornerstone of Black’s larger library of more than one thousand volumes.

Accompanying this post are images of several pages featuring Black’s underlinings and annotations.

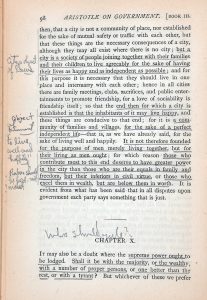

Black habitually wrote in his books, commenting on passages that he liked or disliked, summarizing texts, and pointing out ideas, facts, or passages for future reference. The pages seen here from Black’s copy of Aristotle on Government reflect his lawyerly interest in practical abstractions. See page 98 for his brief observations: “City—object of law,” “Object of Government to live well and happily,” and “Rulers should be best, not richest.”

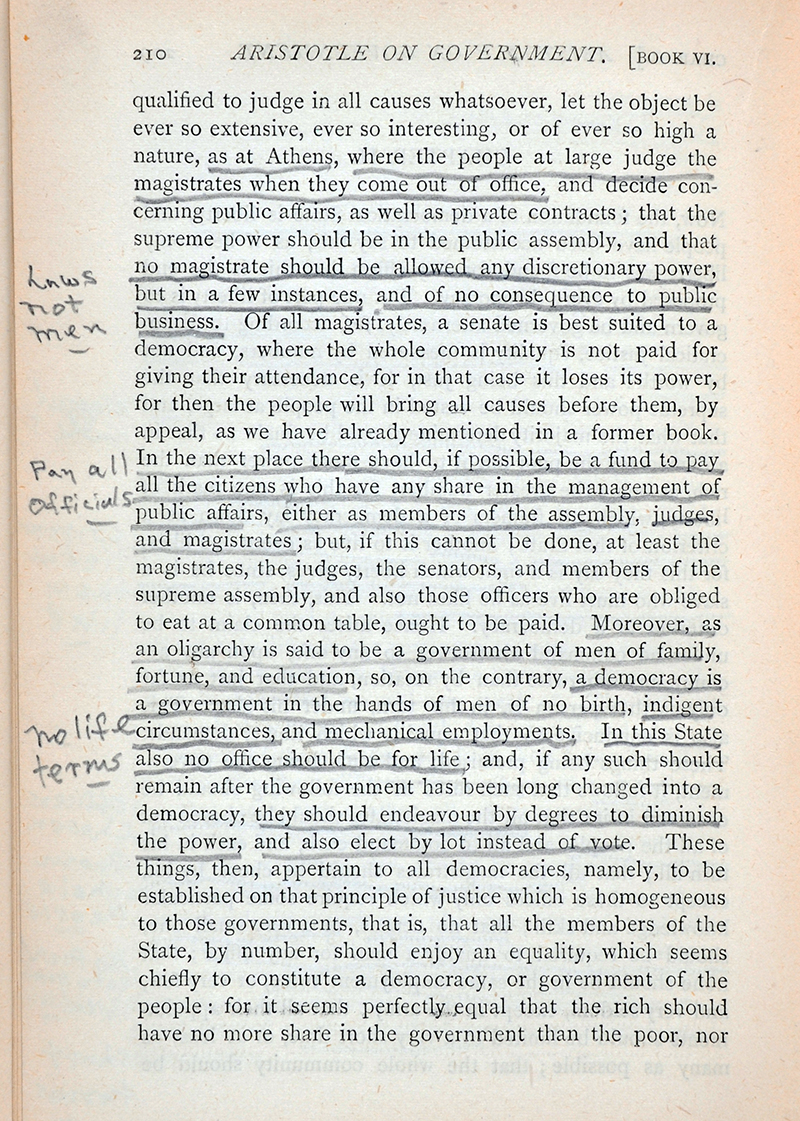

As Aristotle turns to practical instructions concerning governance (p. 210), Black’s marginalia matches the philosopher’s didactic mood: “Laws not men” (for a passage arguing against giving magistrates discretionary powers), “Pay all Officials,” and most pointedly, “No life terms.” This last annotation, sadly, gives us no idea what Black, the holder for a lifetime appointment, actually thought about Aristotle’s advice.

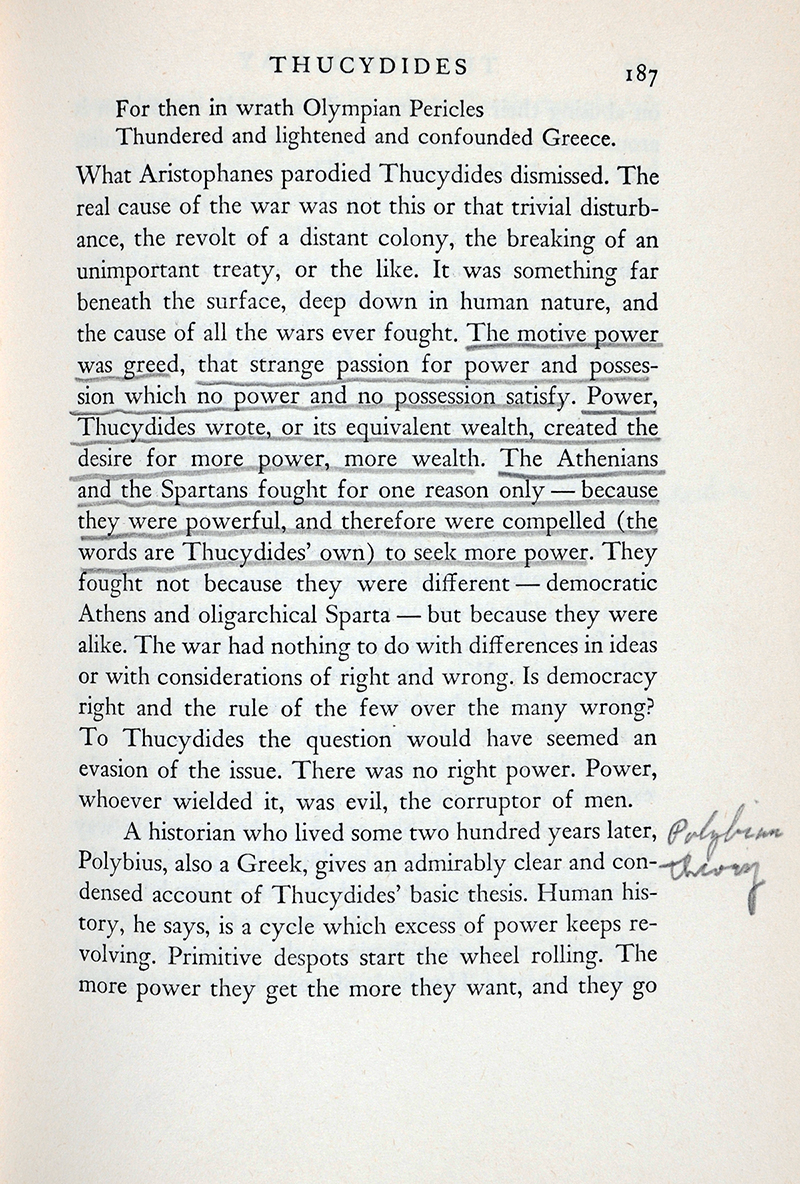

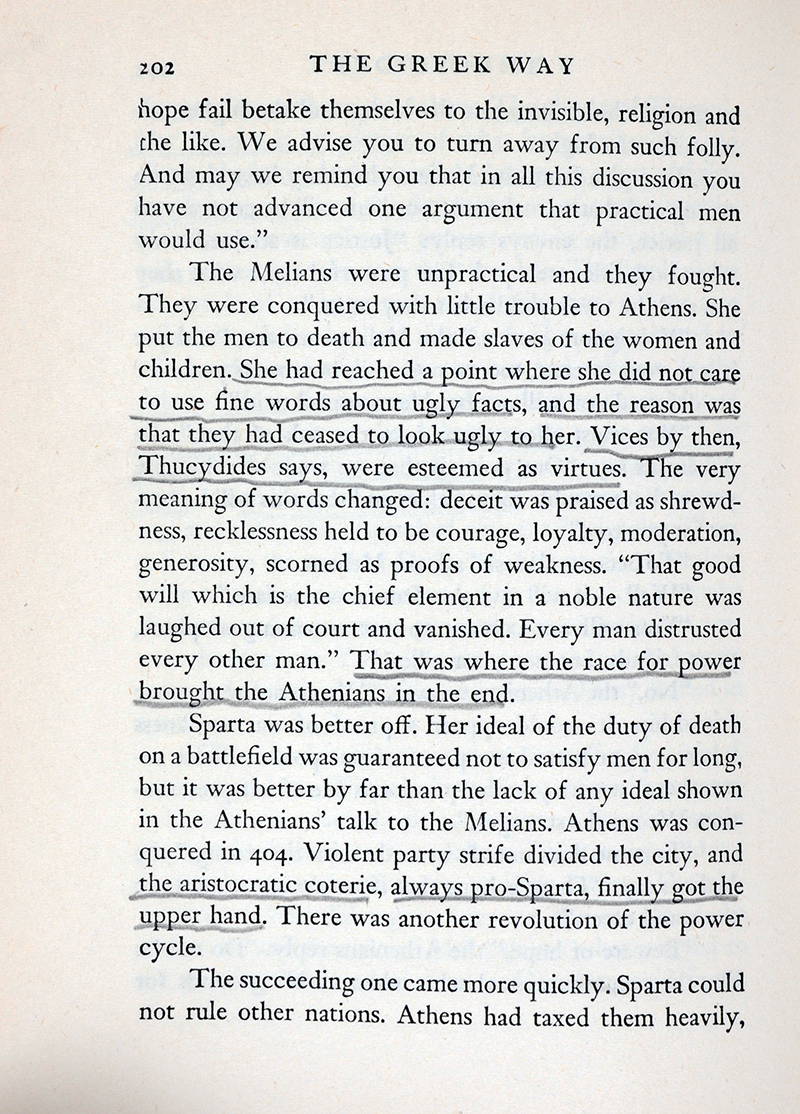

Reading Hamilton’s commentary on Thucydides (p. 187), Black singled out a passage of some eight lines which eloquently discusses “greed, that strange passion for power and possession”—a complicated emotion that is, according to the author, at the root of all wars. Similarly in The Greek Way (p. 202), Black singles out a passage which, though written in Hamilton’s conversational style, constitutes a solemn warning to the powerful Democratic states of Black’s times—or of our times.

“She [Athens] had reached the point where she did not care to use fine words about ugly facts, and the reason was that they had ceased to look ugly to her.”