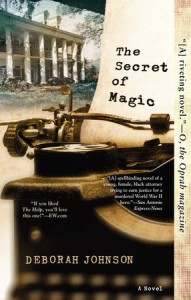

Our readers may be aware that the University of Alabama School of Law is co-sponsor, with the American Bar Association, of the Harper Lee Prize for Legal Fiction. The winner for 2015 is Deborah Johnson’s powerful and evocative novel The Secret of Magic, set in post-World War II Mississippi. The following is an appreciation of The Secret of Magic, contributed by essayist and literary critic Philip D. Beidler, who is the Margaret and William Going Professor of English at the University of Alabama.

“An Appreciation of The Secret of Magic”

As someone whose favorite twentieth century American novelists are F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zora Neale Hurston—and who themselves, to my thinking, in The Great Gatsby and Their Eyes Were Watching God, came close to stylistic perfection—I was gripped from the first sentences onward by Deborah Johnson’s The Secret of Magic. It was a text possessing from the outset that rare thing writers talk about—voice; an author in command of a style; in this case not first-person witness, as in Fitzgerald, free indirect speech, as in Hurston, or childhood reminiscence, as in Harper Lee. Here in The Secret of Magic, we encounter the familiar omniscience of traditional realism, but with a stunning versatility—narration, description, dialogue, interior monologue, along with flashback, jump cut, interweavings of parallel texts. Altogether it makes for a completeness of what Henry James called “density of detail, solidity of specification, the air of reality”—or, to cite his fellow combatant in the realism wars, W.D. Howells, the world brought back to us “in faithful effigy.”

As someone whose favorite twentieth century American novelists are F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zora Neale Hurston—and who themselves, to my thinking, in The Great Gatsby and Their Eyes Were Watching God, came close to stylistic perfection—I was gripped from the first sentences onward by Deborah Johnson’s The Secret of Magic. It was a text possessing from the outset that rare thing writers talk about—voice; an author in command of a style; in this case not first-person witness, as in Fitzgerald, free indirect speech, as in Hurston, or childhood reminiscence, as in Harper Lee. Here in The Secret of Magic, we encounter the familiar omniscience of traditional realism, but with a stunning versatility—narration, description, dialogue, interior monologue, along with flashback, jump cut, interweavings of parallel texts. Altogether it makes for a completeness of what Henry James called “density of detail, solidity of specification, the air of reality”—or, to cite his fellow combatant in the realism wars, W.D. Howells, the world brought back to us “in faithful effigy.”

One more invocation, perhaps the most relevant here, might be Conrad. The task of fiction, he famously once said, was “to make you see.” Accordingly, from the beginning, for all its commingled sadness and horror, Johnson’s narrative makes a claim that the reader must not be allowed to look away. A black, highly decorated World War II lieutenant returning in uniform to his home in the fictional town of Revere, Mississippi, is dragged off a bus at the Alabama Mississippi state line, for refusing to give up his seat to a while German prisoner from a nearby internment camp, and savagely beaten to death. A young, black, female civil rights lawyer from New York is summoned to investigate the circumstances of the crime and its quick dismissal in the local courts. The author of the invitation is an aging, eccentric, white aristocrat famous for a best-seller about the childhood adventures of white and black playmates that has made her a cult author in literary circles and a political pariah banned in her own state.

Johnson’s book, meanwhile, reveals its own literary ambitions as a classic of current stylistics and textual practice. In an old phrase from high-school English, one might begin by calling it a roman a clef—a novel with a key. Thurgood Marshall is a major character. Mary Pickett Calhoun, private, reclusive author of the original Secret of Magic, bears more than an occasional resemblance to Nelle Harper Lee. The young female attorney is modeled on the pioneering Civil Rights figure Constance Baker Motley. The murder of a decorated black veteran is based on an actual incident. As to technical sophistication, this adds up to something more like what we would now call a nonfiction novel. There are imaginary conversations, out-of-life adventures, a complex dramatic structure. Meanwhile this is all combined with what is frequently called magical realism or literary metafiction. Most important is the plot whereby the titular book The Secret of Magic, by Mary Pickett Calhoun, has set the larger novel we are reading, Deborah Johnson’s The Secret of Magic, in motion. The two books then weave in and out of each other until seamlessly converging at the conclusion.

Further, this is no trick of postmodern grandstanding. This is the work of an author of intense literary authority, and of intense moral authority. I could not help thinking, as I read of Peach, Willie Willie, Mr. Lemon, and the children of the Magnolia Forest, of Toni Morison in Song of Solomon. with Milkman, Guitar, Pilate, Hagar, and the old legends of the flying Africans. On a more direct note, I thought of the blood-chilling bus trip with which the novel opens: Tuscaloosa, Gordo, Ethelsville, westward into the Tombigbee towns of Mississippi. I have traveled that road all my adult life. But I never managed to realize as a white person from outside the South just how god forsaken it could be for a black person in the pre-Civil Rights era—or the standard post World War II southern town, the white gentry, the ancient black retainers, the sheriff, the judge, the lawyers, the feral, knuckle-dragging courthouse idlers. I had suspicioned what it was like from Harper Lee, Scout, Jem, Dill, Calpurnia, Atticus, Tom Robinson, and the Ewells and the Cunninghams. I had tried to imagine it on many trips to Maycomb/Monroeville. I had wondered. Now I felt it. Deborah Johnson had made palpable the hatred and the silent terror—the dread undertone of what Houston Baker has called the Long Black Song.