The following text and images are taken from an exhibit titled, “A Little Renaissance of Our Own.” That exhibit was first shown several years ago, and was remounted in our Special Collections reading room in October 2014. Our efforts to acquire materials from this era are ongoing, as this exhibit shows, but it also reflects works added decades ago, thanks to the initiative of the late Professor John C. Payne, for whom our reading room is named.

The Tudor-Stuart Era was a time of upheavals and transformations. Henry VII seized power (1485) as a feudal monarch, ruling over a manorial economy. Spiritually, most Englishmen lived within the framework of medieval Catholicism. Two centuries later, the overthrow of James II (1688) saw England governed by a constitutional monarchy with far-flung commercial and colonial empires. Intellectually, the English had been influenced both by Renaissance humanism and the turbulent reformism of the Protestant Reformation. The latter contributed to the rise of Parliament as a counterweight to the absolutist Stuart Kings James I (1603-1625) and Charles I (1625-1649).

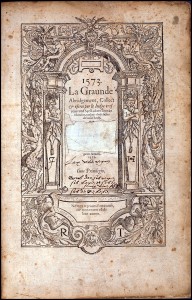

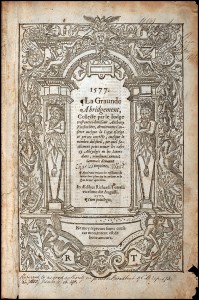

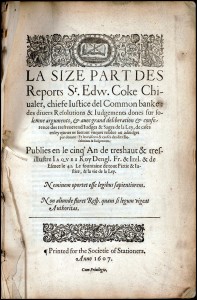

English law had changed too; but as law is a conservative discipline, it should not be surprising that law writers sought to reconcile medieval common law (obsessed with title to land) to a new world of trading ventures. The task was to digest and restate, beginning with Thomas Littleton’s Tenures (1481 or 1482), continuing through variants of La Graunde Abridgement (from 1516), and culminating in the works of Edward Coke, notably his thirteen volumes of reports (from 1600) and his four-volume Institutes (1628-1644). F.W. Maitland said of Coke’s ex post facto medievalism that “We were having a little Renaissance of our own, or a Gothic revival if you please.”

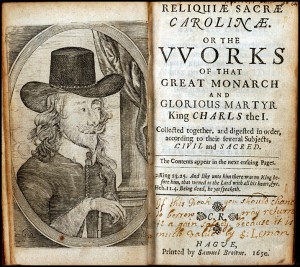

This exhibition includes three grand abridgements (1573, 1577, 1675) and several editions of reports, including Coke’s Size Part (1607), Thomas Ireland’s abridgement of Coke’s Reports (1651) and Henry Yelverton’s Reports (1661). Likewise, there are practice aids such as the wonderfully titled Simboleography (1603), a study of “Instruments and Presidents.” Finally, on display are historical works (a 1640 Bracton, a 1673 Glanville) and one polemic—the 1650 Reliquiae Sacrae Carolinae, published a year after Charles I’s execution at the hands of Parliament, and devoted to “that Great Monarch and Glorious Martyr.”

Printing styles range from the glorious Renaissance presentations of Richard Tottel to the balanced lines of Restoration craftsmen whose fonts anticipated those of the Enlightenment. The volumes range in size from folios to duodecimo pocket books. The Charles I reliquary is one of the latter—published at the Hague and no doubt carried as discreetly as possible by its readers in England.